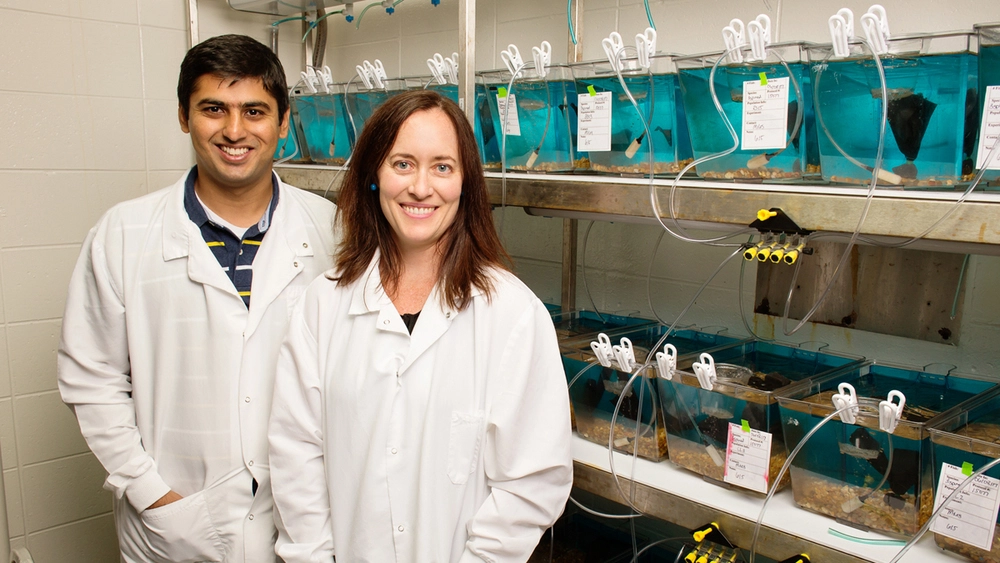

Work led by Alison Bell, professor in the department of Evolution, Ecology and Behavior, found that the transition to fatherhood is accompanied by a host of changes in gene activity in the brain. The study, published in Nature Communications, focused on male sticklebacks because they, rather than female sticklebacks, provide parental care to eggs and fry. Graduate student Abbas Bukhari was first author of the study.

“The male stickleback defends the territory, he builds the nest, he attracts a female to spawn . . . and the nest is everything to him: it's where his babies are, it's the center of his territory,” Bell said, describing the changes experienced by stickleback fathers. “Then the eggs hatch after about a week; he's still defending a territory, he's still protecting his kids, he still has a nest, but all of a sudden he's interacting with his offspring in a different way compared to when they were just eggs.”

In some ways, a male stickleback is quite like any other new parent; he must abruptly shift his behaviors from focusing on his own biological needs to prioritizing the protection and care of his relatively helpless young. Stickleback fathers fan to circulate water past their fertilized eggs, keep the nest clean, protect the young from predators, and retrieve wandering fry that stray from the nest. They must exhibit nurturing behavior toward their offspring while still mounting a rapid aggressive response toward intruders that may pose a threat.

Despite this dramatic behavioral transition, stickleback fathers are distinguished from their mammalian counterparts whose neural response to parenthood has been extensively studied: females who gestate their young and lactate to feed them—physiological events that are accompanied by well-documented suites of swift hormonal changes. Yet Bell and her colleagues knew that even though stickleback dads do not experience these events, dramatic physiological changes were still occurring.

“The cues that these dads are getting, they are exogenous, they're not inside his body; these are eggs that are in his nest,” Bell said. “It's something that's happening exogenously and socially.”