A team of plant biologists has made an exciting discovery about how flowers grow and organize themselves, and one of the key authors was Assistant Professor in Plant Biology Ya Min (Minya) from the University of Illinois. Their new study, published in the journal Current Biology, explores how a gene called CYCLOIDEA (CYC) helps shape the early development of a wildflower known as Mimulus parishii (commonly known as monkeyflower). This gene is important because it helps the flower decide which side will become the “top,” setting the stage for the plant’s final form.

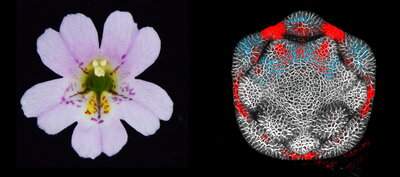

To study this process, the researchers used glowing marker genes and advanced fluorescent imaging tools that allowed them to watch CYC turn on and off inside tiny flower growth centers called meristems. They found that CYC follows three major phases. First, it switches on very early—before hormones like auxin appear—and it does so on the top side of the flower-to-be. Next, as the meristem grows and auxin begins forming patterns, CYC stays in its dorsal, or top, position in normal plants. But in mutant plants missing a regulator called blade-on-petiole (BOP), CYC spreads out instead of staying focused, showing that BOP plays an essential role in keeping CYC in the right place as the flower develops. In the final phase, auxin and BOP work together to sharpen and stabilize the CYC pattern, ensuring the flower forms proper left-right symmetry.

This research is significant because it helps explain something familiar yet scientifically complex: how flowers get their forms. Flower shape affects how plants attract and interact with pollinators, which influences ecosystems, food webs, and even crops that humans depend on. By understanding the timing and teamwork of genes like CYC, scientists gain insight into how plants adapt and evolve, especially plants and pollinators could react to the changing environment differentially. These discoveries may one day help plant breeders develop new varieties with improved resilience or better pollinator attraction.

Overall, Professor Minya and her colleagues have shown that behind every flower’s shape lies a careful sequence of genetic and hormonal signals. Their work helps us appreciate the hidden processes that allow plants to create the diverse and beautiful blooms we see in gardens, fields, and natural landscapes.