We are thrilled to announce that five graduate students from the School of Integrative Biology (SIB) have been named semifinalists in this year’s Image of Research competition! Each year, this exhibition showcases the stunning diversity and creativity of graduate student research.

We invite you to explore the online exhibition and cast your votes for your three SIB favorite entries. Your votes will help determine the People's Choice winner, who will receive a $100 award. Voting closes on Friday, April 11.

You can also view the exhibition in person on the second floor of the Graduate College during Graduate Student Appreciation Week (April 7-11). Stop by anytime between 9 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. to see these incredible research images up close!

Looking out the front door by Entomology Graduate Student Timo Wayman

My work focuses on Bee Hotels, which are artificial nesting structures for bees that in nature would nest in cavities such as beetle holes and snail shells. Bee hotels have been marketed to gardeners as a way to help bees but there is evidence they could help promote parasites and invasive species. I collected bee hotels from gardeners across Illinois to investigate and I am just now wrapping up rearing bees like this one from them. I had the bees emerge into deli cups from each individual bee hotel hole so I could identify which species were associated with which parasites.

Beneath the Pines by EEB Graduate Student Amanda Martinez

The Louisiana Pinesnake (Pituophis ruthveni) displays distinctive morphological adaptations, including a laterally compressed cranium and an enlarged rostral scale that facilitate its burrowing capabilities. These features underscore its specialization for a subterranean lifestyle, rendering it one of North America’s rarest snakes. It inhabits the longleaf pine savanna, a fire-dependent ecosystem sustained by periodic, low-intensity burns. Louisiana Pinesnakes maintain a close ecological association with Baird’s pocket gophers (Geomys breviceps), which serve as their primary prey and provide extensive burrow systems that function as refugia and hibernacula. Widespread habitat loss during the 20th century led to the near-extirpation of the Louisiana Pinesnake across its historical range, necessitating targeted conservation efforts. The release of captive-bred yearlings into restored longleaf pine forests has been a significant milestone in recovering this critically endangered species. My research supports these initiatives by generating critical genomic data, including estimates of gene flow, inbreeding, effective population size, and genetic diversity. These metrics guide captive breeding programs and inform reintroduction strategies. Additionally, environmental DNA sampling provides a non-invasive tool to monitor P. ruthveni across its fragmented range, leveraging soil analysis to advance data-driven conservation efforts.

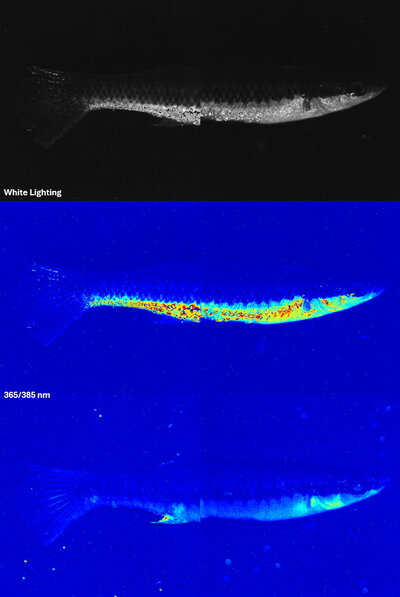

When You See Their True Colors: Secret Ultraviolet Signaling in Fish by EEB Graduate Student Anne Aka

Edgar Degas once said, “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” Under the sun’s natural light, most Midwestern fish appear dull and ordinary to humans compared to their brightly colored counterparts in the ocean or tropics. But, there may be more than meets our eyes. The naked human eye can only detect light between 400-700 nanometers, making ultraviolet (UV) light (100-400 nm) invisible to us. However, some wildlife have photoreceptors that detect UV rays (usually within the 350-400 nm range). This includes local fish in the Boneyard Creek running through the heart of the University of Illinois campus. My research dives into the diversity of UV color patterns and visual sensitivities for species occurring in the same population and visual environment. As shown in this image of a Blackstripe topminnow under UV and white light, there is much to unearth in the secret world hidden right in front of our eyes. If people have different perspectives on the same painting, imagine the different views our little friends experience from the same scene swimming down the stream. What colors can they truly see? And what/how do they communicate with those private displays of color?

The Melting Arctic: A Fleeting Beauty by Plant Biology Graduate Student Lijia Guo

As the world warms, the Arctic feels first, its ancient tundra slowly unraveling. Here, in Alaska’s polygonal landscape, thawing permafrost reshapes the landscape—collapsing paths, shifting waterways, and rewriting the patterns etched by ice over millennia. The photo captures a breathtaking aerial view of Alaska's polygonal tundra, a fragile and extraordinary landscape sculpted by the processes of permafrost. During the summer, we ventured into this remote and pristine expanse, conducting field sampling and excavating deep into the permafrost to analyze its secrets. Our lone tent, dwarfed by the endless tundra, feels like a metaphor for humanity itself—tiny and fragile against the vastness of nature, yet carrying the weight of its future. The crystal-clear pools mirror the endless sky, as if the Earth gazes skyward, seeking solace. Nature is both exquisitely beautiful and alarmingly fragile, demanding the dedication of generations to preserve and protect it.

Egg-shaped Decisions: The Geometry of Survival by PEEC Graduate Student Facundo Fernandez-Duque

Nestled among cattail stems, this image captures a moment in a Red-winged Blackbird’s (Agelaius phoeniceus) life, juxtaposing nature and science. Alongside real eggs rests a 3D-printed model—designed to test how angularity influences a bird’s decision to reject or accept foreign objects in its nest. My research explores the intricate interplay of shape and color in avian egg recognition, shedding light on how species like Red-winged Blackbirds adapt their behavior to balance parental investment with brood parasitism defense. This particular angular model represents the most extreme deviation from natural egg shapes, provoking a reaction that reveals the bird’s sensory and cognitive thresholds. Through experiments like these, we gain insight into the coevolution of hosts and parasites and the mechanisms underlying survival strategies in the wild. Just as the lines between art and science blur in this photograph, so too does this research bridge ecological theory and biological innovation, revealing the delicate geometry of survival.